War Child today still emphasises the charity’s historical connections with the music world, but one of the first money-raisers for our work involved animals.

Over the 1993 August Bank Holiday we organised a three-day event at London Zoo. There were sitar and sarangi players near the elephants, Peruvian pipers serenaded the llamas and didgeridoo players the kangaroos. There were African drummers and giraffes, gamalan players entertaining the Indonesian rhinoceros, Brazilian berimbau players and the squirrel monkeys. The Chinese percussionists were kept well away from the giant panda, Ming Ming, because she needed all her concentration to breed.

The most amazing sights for me were a string quartet playing Bach in the Butterfly Grotto and a lone cellist in the shadowy depths of the Aquarium entertaining the circling sharks.

On the lawns, pathways and courtyards there were clowns, jugglers, stilt walkers, magicians, dancers and acrobats, storytellers, poets and pavement artists. Inside the monkey house we held children’s workshops, art and photo exhibitions.

The promotional brochure said that ‘during these three days, London Zoo, with the help of its animals, will come to the rescue of another endangered species – children threatened by the 30 wars raging across our planet.’

One of War Child’s first money-making fundraisers was not with Pavarotti, Bono or Brian Eno, but thanks to Sue Lloyd-Roberts. As a BBC investigative journalist, Sue travelled to Mostar several times to report on War Child. On her first visit, she was travelling with a War Child convoy when it got shot up. I was in London and was rung up by the BBC to be told that their correspondent had been forced to take refuge in a ditch. She said of her experience, ‘the part of my brain that recognised fear doesn’t exist. In such situations people scream or pray, but I picked up my camera’.

This didn’t stop her organising a fundraiser for War Child, ‘Bop for Bosnia’, which took place at the BBC TV Centre in February 1994. Sue recruited Chris Jagger as the musical director and Dave Gilmour, Leo Sayers and Ron Kavana were among the performers. As well as live music, there was a dinner and auction and she helped raise a few thousand pounds for the charity.

It was early 1994 when Nigel Osborne arrived in Mostar carrying a large bag full of percussion instruments. A big, bearded bear of a man, Nigel was Professor of Music at Edinburgh University. He’d heard that we were co-operating with MTV and taking music tapes into Sarajevo where he’d been organising music workshops with the Sarajevo String Quartet and collaborating with the poet Goran Simic on two children’s operas.

He said he would like to run workshops in East Mostar in what was to be the start of a long association between Nigel and War Child.

It was no problem gathering interest. I had been amazed how quickly news travelled across this bombed-out ghetto and, in such a desperate place, anything out of the ordinary was news.

After two years of shelling, the upper floors of the UNHCR building had been blown away. The lower floors, housing the UN office, were as secure as it got in East Mostar. By the time Nigel arrived, there were 20 children and their parents. They sat very quietly and few of the children smiled. They looked as though they were about to be told bad news, not be offered the chance to bang drums and blow whistles. I looked around the room and realised most of them would have had no memory of anything but fear.

One mother sat with her blind, impassive, six-year-old daughter. I watched while Nigel tried to get the girl to play a triangle. She refused to hold it. This went on for some time until, finally, she grabbed the triangle with one hand, the metal stick with the other and struck it over and over. Her face lit up. Her mother told us that it was the first time she had seen her daughter smile in over two years.

War Child were able to develop and extend Nigel’s work because an unannounced visitor turned up at our Camden Town office a few weeks before this workshop. Brian Eno’s manager and wife, Anthea, heard Juliet Stevenson talking about War Child on the radio and turned up at our office with a cheque for £2,000. She asked if the money could be used for music aid for the children of Bosnia.

Her arrival was a turning point. We had our first funding for music workshops and a door had been opened that led us to Brian and other major figures in the music business.

Bill and I wanted to let the Enos know what their support could achieve. They took us out to dinner in Notting Hill and we told them about the workshop and the little girl. That evening Brian and Anthea suggested we should think about raising money and support for a permanent music centre in Mostar.

Brian had never been involved with charities. Ten years before, he had scorned Band Aid, admitting that he had been cynical about ‘egocentric compassionates’ who made themselves feel better by helping people about whom they knew nothing. I asked him why he had changed his mind with his support for War Child and he told me that Anthea had influenced him.1

She had been involved with the Nordoff Robbins music therapy charity and was keen to reroute money flowing there from the music business to help the children of Bosn about the issues involved in the wars in former Yugoslavia, but liked what he’d been told about our work: a charity, Anthea told him, which operated by the ‘seat of their pants’. Under these circumstances, helping children seemed pretty uncontroversial.

Brian agreed to join Brent Hansen, Head of MTV Europe, Tom Stoppard and Juliet Stevenson as a patron. He didn’t come alone, persuading David Bowie to join him. And he and Anthea didn’t come without a plan.

Anthea set up a think tank to generate ideas as to how funds could be raised for War Child and our Mostar plans. We had fortnightly meetings at her Roland Gardens flat. There were Anthea and I, Brian’s assistant Lin Barkass, Paul Gorman, Jeremy Silver and Rob Partridge. They all came with excellent pedigrees. Paul wrote for Music Week and Mojo, Jeremy was head of A&R at Virgin Records and Rob had set up his own music PR company after managing Bob Marley and U2.

The team got to work on the first fundraiser which we decided to call ‘Little Pieces from Big Stars’. Music and art celebrities were asked to contribute something, the only condition being that they had to make it themselves and it had to be small.

In September 1994 the exhibition of 150 works opened at the Flowers East Gallery in Hackney. It included contributions from the two McCartneys: Paul’s 2” x 2” driftwood carving and four of Linda’s photographs. David Bowie exhibited 17 computer-generated prints. Bono, a music box containing sunglasses. Charlie Watts, a drawing of a hotel telephone. Billy Bragg, a brass rubbing of a manhole cover. Pete Townsend, a 2.5” x 2” model of a Rickenbacker guitar.

Brian surpassed them all with six contributions, including four sculptures made from plaster and nails: ‘Ancient Head’, ‘Nude in Light Victorian Snowstorm’, ‘Siren’ and ‘Fruit Prison’, and a Japanese forest ambient recording played on a camouflaged cassette player.2

After a two-week exhibition the pieces were auctioned at 140 the Royal College of Art. Paul McCartney’s contribution alone sold for over £12,000. The evening resulted in a £70,000 donation to War Child.

In less than a year, we’d come from wondering how to pay our office overheads and trips to Sarajevo and Mostar to a situation where we were feeding thousands of people a day and a piece of driftwood could make the charity £12,000. It didn’t stop there.

Nine months later, Anthea and Brian’s office organised ‘Pagan Fun Wear’, described by Brian as being one of the ‘all- time weird events in London’s recent cultural history’. The idea was to model costumes designed by pop stars which would then be sold at auction to benefit War Child.

As with ‘Little Pieces’, Anthea and Brian’s small staff at Opal coordinated the event. They recruited 35 big names from the music and design worlds, 45 garment and shoemakers and 30 models, organised the catering, music, permissions from 17 recording companies, ticket sales, production and publicity.

I wondered how Brian was coping with his life as a musician and producer. Everything seemed to have been put on hold to cope with these extraordinary events.

Iggy Pop designed penis sheaths; Jarvis Cocker modelled his own shoes; David Bowie contributed ‘Victim Fashion’, which consisted of a model wrapped up in bandages; John Squire designed his own underwear; Brian, his coat and pants; Dave Stewart, a bikini and mac. Other contributors included Bono, Adam Clayton, Michael Stipe, Phil Collins, Bryan Ferry, Anton Corbijn, Laurie Anderson, Joan Armatrading and Jaron Lanier, one of the pioneers of virtual reality.

Getting everything together was a nightmare. Iggy Pop’s design for his penis sheaths came by fax with scrawled and difficult-to-decipher graphics. They were to be three feet in length and made of multi-coloured papier mâché. All these ideas were then manufactured by students from the London School of Art and Design.

Last, but not least, everything had to be modelled on the big night which concluded with an auction of the designs. Paul Gambaccini and Janet Street-Porter hosted the evening. The event raised more than £200,000.

‘Pagan Fun Wear’ was held at the Saatchi Gallery in St John’s Wood. They didn’t normally let this out for non-gallery events, but Brian had promised them there would be no damage. As he walked around at the end of the evening, he saw that the floor and walls had been squirted with jets of black poster paint. They had been taken from a room being used by Damien Hirst for his spin paintings. Brian spent the rest of the night scraping this off.

When he told me later about the paint, I was horrified. Being Brian, he didn’t tell any of us at War Child. If I’d known, I would have helped.3

I thought that we would be very lucky to benefit from further Opal money-raisers, but I need not have worried. Thanks to the Enos, we’d hardly started. They had opened a door to the music world that was to result, not only in further funding, but to the dream of the music centre being built.

In August 1995 I was asked to speak at a demonstration in Trafalgar Square in support of the right of Bosnians to defend themselves. Other speakers included Michael Foot and Brian. As a director of War Child, I was breaking British charity law by speaking politically. I said: ‘I would like to speak on behalf of the young people of Bosnia. They are like young people everywhere. They take pleasure in music. They party, they study and are interested in all that is happening beyond the prison of their war. They have the anger of youth and they can love like only youth can love. Something I will never forget is the sight of young girls watering the flowers on the graves of their dead boyfriends in Mostar. Where indeed have all the flowers gone? They are covering thousands of graves of young people in south-east Europe. It is the young who die when they are the ones who should live. It is the teenage soldiers who die on the front line, rarely their older commanders. In this war, it is the child who is killed because it is the child who plays in the street. This is a war of the calculated and deliberate targeting of children.’

Tony Crean of Go Discs!, the record company that represented Paul Weller and had recently launched the band Beautiful South, happened to be walking through the square. He had been recovering from flu and later told The Times, ‘For once, I was getting further into the papers than just the sports pages – watching more television than normal too – I was reading about ethnic cleansing and mass graves, seeing genocide on the tea-time news – I realised that I didn’t really understand what was going on.’

A few days later, we got a call from Andy Macdonald, the head of Go Discs!, to come and see him and Tony. They had an idea for helping War Child: to bring together musicians and record an album on one day, a Monday, and release it the following Saturday.

What was to become the Help album had more than 20 artists, including Oasis, Blur, Radiohead, Orbital, Massive Attack, The Stone Roses, Neneh Cherry, Sinéad O’Connor, Paul Weller, Paul McCartney and Portishead. It was recorded on Monday, September 4th, 1995, in studios across Europe and released, on target, five days later.

Help sold over 70,000 copies on the day of release, becoming the fastest-selling album in British music history. The artists and Go Discs! waived royalties and Help raised more than £1.5 million. Brian produced the album and was responsible for making sure the recordings were ready for pressing in time for the Saturday release. Racing against the clock, he said of the experience, ‘Enjoyable panic, but I went into Hitler mode in the last few minutes.’

The income from the album was used to provide artificial limbs for wounded children, food and clothing to orphanages, the purchase of a refrigerated truck to supply insulin, funding for school meals in central Bosnia, support for a mobile medical clinic in Bihac , the supply of premature baby units to Banja Luka, as well as baby milk, contraceptives and even funding for mine clearance programmes. Linda McCartney supplied 22 tonnes of her veggie burgers which we delivered to three Bosnian cities. Help monies were also used towards the running of the War Child bakery and to expand the charity’s music programmes.

That summer, Brian had been working with U2 in Dublin when the phone rang. It was Luciano Pavarotti inviting Bono to perform with him at the ‘Pavarotti and Friends Concert’ that September. When Brian told Anthea about the call, she persuaded him to get Bono to take part and do it for War Child. Pavarotti’s partner, Nicoletta Mantovani, then came to London and met with Anthea. Nicoletta was soon to marry Pavarotti and was to prove instrumental in winning and retaining the Maestro’s support for War Child.

Anthea told Nicoletta about War Child’s music work in Sarajevo and Mostar and said that she and Brian had been discussing the construction of a music centre for children in war-shattered East Mostar.

Nicoletta said that Pavarotti had been looking for a project to support in Bosnia and that the suggestion might appeal to him. It did and the result was that he became a patron of War Child and the next ‘Pavarotti and Friends’ concert would be held to make the idea into a reality.

The concert took place at Modena’s Parco Novi Sad on September 12th, 1995. Pavarotti, Bono, The Edge and Brian performed ‘Miss Sarajevo’, a song Bono had written for the event and which became a hit single. The words were about the young women of Sarajevo who had staged a beauty contest at the height of the war. Lined up in swimsuits with the crowned Miss Sarajevo in the middle, they carried a banner. DON’T LET THEM KILL US.

When I heard Pavarotti come in over Bono’s voice singing, ‘Is there a time for high street shopping, to find the right dress to wear, here she comes with her crown,’ there was a lump in my throat. I remembered Jasmina and her boyfriend’s poems, resigned to being killed, but not willing to be defeated.

Other performers at that concert included Meat Loaf, the Chieftains, Dolores O’Riordan of the Cranberries, Zucchero, Jovanotti and Simon Le Bon. I sat one row behind Princess Diana and watched him flash his eyes at her the whole time he was on stage.

Afterwards, I walked backstage to find Pavarotti holding Anthea’s hand and singing ‘Happy Birthday’ to her. There were three tenors serenading her, but the other two were not Placido Domingo and José Carreras. They were The Edge’s and Bono’s dads.

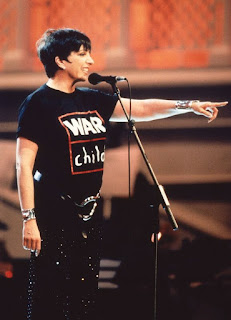

The following year Pavarotti held the second concert in aid of the music centre. In June 1996 the musicians included Eric Clapton, Joan Osborne, Elton John, Liza Minnelli, Sheryl Crow and Zucchero. Clapton sang ‘Holy Mother’, and Liza Minnelli, in a War Child T-shirt, joined Pavarotti for ‘New York, New York’.

In the finale, Elton John and Pavarotti sang ‘Live Like Horses’ and were joined by the other artists from the show. The audience of many thousands waved banners declaring PEACE, NOT BOMBS.

As the TV boom camera swung over our heads, I had the feeling that music can make a difference to the world. The last time I had felt this was when I was standing in cellars in Mostar during the war, with children singing and drumming to the background sound of shelling.

After the concert Anthea said, ‘We’ve had an idea for another fundraiser. We want to get music stars to make art works on the theme of a musician or band inspirational to their own work.’

‘Milestones’, which was held in February 1997, involved, as Brian put it, ‘the usual suspects’. Pavarotti sent a handkerchief on which he’d drawn Enrico Caruso. Graham Cox of Blur did an homage to Syd Barrett of Pink Floyd. Paul McCartney, a drawing of Buddy Holly, aged 60. Bono’s inspiration was Frank Sinatra – a music box containing Jack Daniels, shot glasses and a blue napkin. It was signed ‘To Frank, Love, Bono’.

Yoko Ono contributed her bronzed ‘Lennon eyeglasses’. Bob Geldof celebrated the Rolling Stones with a wall-size London map that included a River Thames with moving water. Bowie’s tribute was to the Walker Brothers. Sinead O’Connor’s was to Bob Marley. Brian contributed his musical dedication to the Velvet Underground, which sold for £40,000.4

With more than 20 contributors, the exhibition was held at the Patrick Litchfield Gallery and the private view and auction at the Royal College of Art.

Lin Barkass, from Brian’s office, summed up her feelings about these fundraisers. ‘Bloody hard work, bloody brilliant, best things I have ever been involved in. People did it all for free, designing, printing, staff at the Daily Mirror running off posters after work, designers from Warner Brothers. Too many good people to name here, like Jenny Ross, Paul Gorman, Greg Jakobek. People had caught the spirit of War Child, that they could all make a difference. If they think they can, then they will.’5

Writing this now, I feel stunned at what we’d been able to achieve. We had received not only significant funding, but also enormous encouragement to use music as a new form of aid to children and young people in conflict situations. We now had the chance to place music at the centre of our aid work.

NOTES

1 Brian Eno: ‘My acquaintance with War Child began with Anthea, who’d been to a meeting and was quite fired up about it. She’d earlier been involved with the Nordoff Robbins Music Therapy charity, and seen how much money was flowing from the music business into that: her plan was to reroute some of that money towards War Child. She volunteered my engagement early on, before I really had a clear picture of what was going on in Bosnia. I’m sure you’ll recall how confusing things were in those early days – it wasn’t clear who was doing what. Anthea remembers that my initial inclination was somewhat towards the Serbs, though I have to say, I don’t actually remember very clearly what I was thinking then. I do remember that Anthea was never in any doubt where her sympathies resided – with the Bosnians. I also remember that a very close friend of mine was a Serb supporter and this may have influenced my position. Anyway, what I realised quite early on was that it didn’t really matter that much who was “right” and who was “wrong”: the fact was that we had a major conflict in the middle of Europe – the first since 1945 – and not much was being done about it. There didn’t need to be any politics involved. War Child was trying to help the child victims of the conflict and that seemed pretty uncontroversial. In time, of course, my sympathies went very strongly towards the Bosnians, not least because of the complete imbalance of power. In time I began to realise that it was the Bosnians who were the pluralists and hence the hope for a fairly shared future. Subsequently we all met up – you, Bill, Anthea, myself, and I think we both liked you and the way you were doing things. It had a “seat of the pants” feel which inspired my confidence.’

2 Other contributors included: Anton Corbijn, four photographs; Vic Reeves, a drawing of ‘Elvis and Frank on Their Way to the Shops’; George Michael, his original drawings for the Faith album; The Edge, a Polaroid ‘Self-Landscape’; Iggy Pop, 16 black-and-white self-portrait photos set one above the other like mug shots for 16 passports; Steve Reich, the first page of his ‘Variations for Winds, String and Keyboards’, three Davidoff cigars, two 18-carat nipple rings, a Ronson cigarette lighter and a Gold American Express card in a distressed resin cast; Joan Armatrading, an ink drawing; Michael Nyman, 36 Sony video prints from an original video of Ayers Rock (he actually sent a VHS of his holiday at Ayers Rock from which were produced the 36 prints). Contributions also came from Boy George, Kate Bush, Nick Rhodes of Duran Duran, Bob Geldof, Shane MacGowan, Adam Ant, Massive Attack and Russell Mills.

3 A Year With Swollen Appendages, Brian Eno, Faber 1996: ‘“Pagan Fun Wear” went brilliantly – just the right balance between gorgeously stylish and improbably improvised. Lots of people came and they all seemed to have had a really good time. Anthea and I worked for two days and nights almost continuously without sleep in the run-up to this – so much to do and so many people to organise. Lynn Franks said this was “the most stylish charity event I have ever been to – and I’ve been to a few.” So it was a tremendous relief at the end of the evening, at 12.30, when it was all successfully over and time to go home. I took one last walk round the various huge rooms of the pristine Saatchi Gallery to make sure no one had left anything behind. I was feeling fine. I’d especially pleaded with the staff at the Saatchi Gallery to use a room they don’t normally let out – a particularly beautiful space. I’d promised them faithfully that there’d be no damage and they shouldn’t worry and my word was my bond etc. “There won’t be any mess at all, I promise you that.” The walls and floor of the room had been squirted with huge jets of black, red, green and yellow paint. It turned out that some of the youngsters who worked for one of the record companies had got drunk and run amok. My heart dropped a thousand miles – and I set about scraping the whole mess off the walls. (It was poster paint, so it couldn’t just be painted over – it would have mixed with the white paint.)’

4 Lou Reed exhibited a small bottle of perfume labelled ‘ODE for Ornette Coleman’, blended by himself with the bottle’s graphics designed by Laurie Andersen. Dave Stewart’s homage was to Bob Dylan. Bryan Ferry’s – Charlie Parker; The Pet Shop Boys’ – Saturday Night Fever; Holly Johnson of Frankie Goes to Hollywood – the Beatles; Karl Hyde of Underworld – Captain Beefheart. John Squire – The Beach Boys. Tim Booth’s homage was to Patti Smith’s Horses.

5 As well as these three major fundraising events, Anthea and her team also organised a set of Christmas cards in 1995 with contributions from Brian, Bowie, Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel, Oasis, Pulp, Iggy Pop, Radiohead’s Thom York, The Blow Monkeys and Dave Stewart.

I just want to share my experience with the entire world on how I got my husband back and saved my marriage… I was married for 5 years with 2 kids and I have been living happily with my family until things started getting ugly with me and my husband that leads us to fights and arguments almost every time… it got worse at a point that my husband filed for divorce… I tried my best to make him change his mind & stay with me cause i loved him with all my heart and didn't want to lose my husband but everything just didn't work out… He moved out of the house and still went ahead to file for divorce… I pleaded and tried everything but still nothing worked. The breakthrough came when someone introduced me to this wonderful, great spell caster called Dr Oniha, Who eventually helped me out… I have never been a fan of things like this but just decided to try it because I was desperate and left with no choice… He did the spell for me and things really worked out as he promised and my husband had a change of mind and came back home to stay with me and the kids. And promise never to hurt me again. We are living happily as it was with the help of Dr Oniha. If you are in need of help you can contact Dr Oniha.

ReplyDeleteEmail :onihaspelltemple@gmail.com

Website: http://onihaspells.com

Call/Whatsapp:+1669223962

Party Bus Rental Service in Las Vegas NV, Affordable Party Bus Rental Service in Las Vegas NV

ReplyDeleteReliable Party Bus Rental Service in Las Vegas NV

https://foxroofinginc.com/

ReplyDeletehttps://foxroofinginc.com/services/asphat-shingle-roofing/